Ambler Road - The line on the land

One Herd in decline. Ecosystems face damage. So, what is the justification of this project? Is it worth it?

Through line: Roads don’t just move ore; they move behavior of caribou, rivers, and people. Put a line on the land and everything else has to decide whether to cross it.

The herd

Fifty years of whiplash. The Western Arctic Caribou Herd is one of the largest herds in Alaska. The population fell to ~75,000 in 1976 after a ~242,000 estimate in 1970. Largely due to over harvesting from humans.

Then in the late 1970’s and 80’s new regulations and management of caribou were put in place and the hunting numbers were pulled back and maintained. In tandem with favorable climate leading to better forage and fewer severe winter icing setbacks, and predator predation not keeping up with the growth, in the early ’90s the herd reached ~450,000 in 1993 and remained steady for a decade.

However, by 2013 the population numbers of this herd slid to ~235,000 by 2013 and ~152,000 in 2023. There are many studies completed by the Alaska Department of Fish and Wildlife on why they are having this decline. It’s been hard to identify but it most likely points to a loss of forage from climate change, and lower cow survival rates.

Caribou cycle, sure, but the current trough is deep and management has already tightened. Wouldn’t more stress continue this decline?

Where the road meets the migration

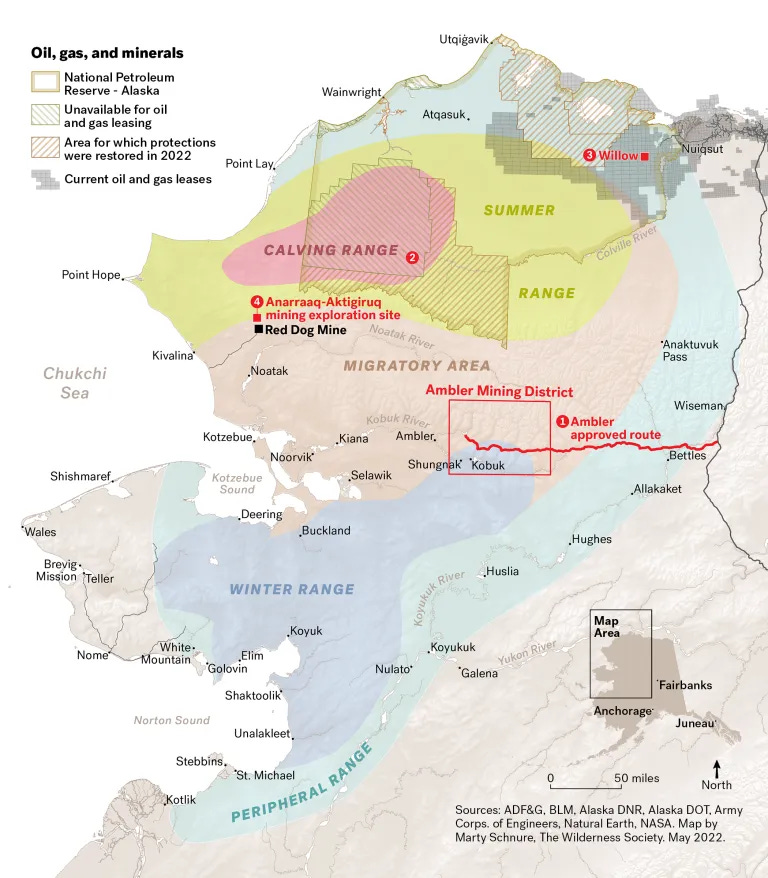

Western Arctic cows push north each spring to calve in the Utukok Uplands. Come fall, the herd spills south and west toward winter range, threading through the Kobuk country. The Ambler road would run east-west along the south flank of the Brooks Range. Right across that movement. Not neatly between “winter” and “calving,” but inside the annual slosh between them.

Noise, traffic pulses, and an industrial bridge on the Kobuk are not theoretical, they’re timing problems in a calendar built by weather and memory.

What does that mean? Expect delay and detour. We’ve seen with other Arctic herds that linear infrastructure can fragment use of traditional corridors or push animals to less optimal forage for days. With Western Arctic Herd already stressed, missed timing in late winter or pre-calving can hit calves and cows hardest. The very group you need to rebound. Source: National Park Service

The water

The project’s would stacks up ~2,869 minor culverts (enclosed, pipe-like structures that carry water under roads), 34 larger culverts, and 29 bridges, with known and assumed crossings of migratory fish streams. Silt and dust don’t obey permits; they obey gravity. The Kobuk is a Wild & Scenic River, and any crossing changes its hydraulics. Done poorly, it chips away at the “free-flowing” value Congress meant to protect. Downstream, Shungnak and Kobuk drink from the Kobuk. So spills or chronic fine sediment aren’t just fish stories, they’re human ones. Source: BLM Eplanning

Zoom out and you’re also driving gravel and salt across permafrost and wetlands, a recipe for thaw slumps, dusted tundra, and culverts that love to clog precisely when a storm wants them most. The maintenance line item isn’t just graders; it’s a promise to fight physics for 50 years.

People aren’t footnotes

Even as a “closed” industrial road, access changes behavior on both sides of the gate. Subsistence hunters in Ambler, Shungnak, Kobuk, Kiana, and Noorvik already chase a moving target as caribou routes shift. A road can push animals off boatable rivers and familiar passes—stretching trips, burning more fuel, and lowering success. The EIS says this out loud: the risk ledger isn’t just ecological; it’s social and economic, too.

So, why build it?

Because the Ambler District is loaded and conveniently aimed at the energy transition. Arctic is a high-grade copper-zinc-lead-gold-silver volcanogenic massive sulfide (VMS - they’re ancient seafloor–hot-spring deposits that got buried, squeezed, and lifted onto land) at feasibility. Bornite (A copper-iron sulfide often called peacock ore because it tarnishes into iridescent blues/purples.) layers on a copper giant with ~88 million pounds of inferred cobalt. Catnip for grids, EVs, and transmission lines that all eat copper. A road turns “stranded” into “serviceable” and, at district scale, could keep production running for decades. Source: Trilogy Metals Inc

However, we don’t have to cut a brand-new road into the Arctic to get copper and cobalt. Big, existing copper hubs, Morenci in Arizona and Kennecott in Utah, already move serious tonnage, while brownfield restarts like Pumpkin Hollow (Nevada) can add near-term supply without new wilderness scars. On cobalt, the Idaho Cobalt Operations (permitted but paused) and Missouri’s re-industrializing sites (US Strategic Metals) offer domestic options, and projects like Talon’s Tamarack (MN) can deliver copper/cobalt as by-products along existing highways and power lines.

Add in fast-growing battery recycling, recovering copper and cobalt from scrap and end-of-life cells, and the “first, lowest-conflict tons” clearly come from existing mines, brownfields, by-product streams, and recycling, not a 211-mile road through caribou country.

If the road is built and performs near its feasibility case, the mine could generate ~$1–1.6B Net Present Value after tax, depending on mineral prices, before corporate decisions about financing, tolls, and any road-use charges. That’s the clearest, current, third-party-audited economic signal. Source: Trilogy Metals Inc.

What’s the tab?

Early Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority flyers pitched ~$350M construction and $8–10M/year in operations and maintenance. BLM’s 2024 Record of Decision refresh put it in a more modern light: ~$672M–$1.28B to build (route-dependent) and ~$12–18.5M/year to keep the plates spinning. That’s before contingencies in a warming permafrost belt. Source: Bureau of Land Management

The choice, in plain English

We do need copper and (some) cobalt to decarbonize. But Ambler is a locked pantry that comes with a trapdoor. A 211-mile industrial road doesn’t blow up the Western Arctic Caribou Herd overnight; it erases it in pencil. A thousand small edits: a late crossing here, a missed calving beat there, extra silt after a storm, a culvert where a bend used to hold fish. Those aren’t rounding errors.

My position: don’t build the road. Get the first, fastest tons somewhere else. Existing mines and smelters, brownfield restarts, by-product copper/cobalt, and recycling, instead of cutting a new line through calving and migration country. The ecological tab isn’t on the balance sheet, and the thing it buys, functioning rivers, intact routes, subsistence that works, are priceless. “Least-conflict minerals” means using what we’ve already disturbed before we redraw another map line across the Arctic.

To me the most ironic aspect of this whole thing is that the administration choose a foreign owned company in charge. They will send some the raw minerals overseas.

If the state forces it anyway, the only honest version is the expensive version:

Full-span bridges over the Kobuk and Reed (no piers in the channel).

Fish-smart crossings at every trickle; real sediment control that’s funded for life, not just year one.

Hard seasonal windows that stop or slow traffic during migration pulses and pre-calving.

Real-time monitoring that triggers slowdowns/halts automatically when caribou stack up.

An Operations and Maintenance bonding budget built for permafrost and failure, not wishful thinking.

That’s what it takes to move ore without moving the herd off a cliff. But given the option, I’d rather move our supply strategy than move the caribou.

Thank you for reading! I highlight threats to public lands and the energy industry’s impact. I believe clean energy is the future, and ALL energy projects should prioritize private land first to keep wild places wild. When energy extraction is needed on public lands all projects must restore the land after extraction. Public lands are unique and once lost, they’re gone forever.