Delay Without Resolution: How California Permits Clean Energy

Soda Mountain Solar shows why California needs faster clean energy approvals and clearer lines on where to build.

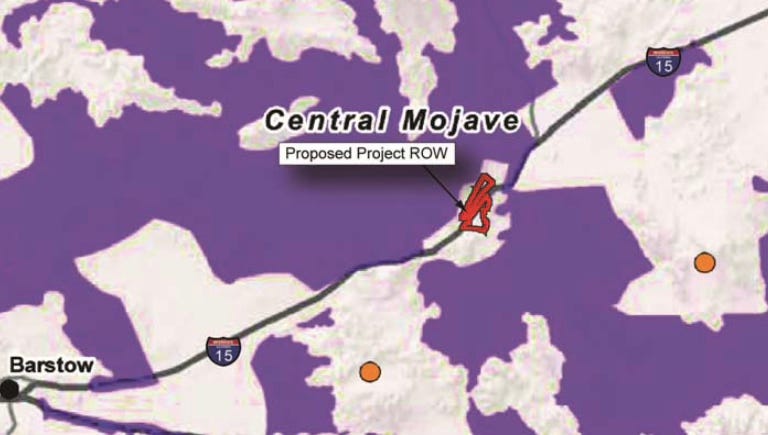

Soda Mountain is a utility-scale solar project proposed on federal land managed by the Bureau of Land Management, about six miles southwest of Baker, in California’s eastern Mojave Desert.

It has been reviewed before.

In 2016, the Bureau of Land Management approved a version of the project after completing a joint federal and state environmental review. That approval described the project area as being close to existing disturbance and infrastructure, including Interstate 15 and nearby utility corridors, which both creates wildlife mortality and acts as a movement barrier. (There are underpasses and overpasses for wildlife along I-15)

However, additional fencing, roads, and activity risk further fragmenting movement for species like desert tortoise and bighorn sheep that occur in and around the area.

The report explicitly noted that desert disturbance is effectively permanent because ecological recovery can take decades. Within that footprint, the area functions as real habitat: surveys documented burrowing owls (active burrows and use for nesting/foraging), desert kit fox dens, and other wildlife using the open valley.

Here is a link to the Biological Resource Report

Today, Soda Mountain is back in review again. This time under California’s newer state-level process at the California Energy Commission, using the opt-in certification pathway created by AB 205.

That alone tells you something important.

California now has faster tools for clean energy permitting.

But the same siting dispute keeps resurfacing.

Supporters argue that Soda Mountain is near existing infrastructure and located in an area already affected by development. They point to the need for large-scale clean energy, prior federal approval, and the urgency of reducing emissions and strengthening the grid.

Opponents argue that proximity to roads and power lines does not mean the land has lost its ecological value. They describe the area as functioning desert, with wildlife movement, sensitive plant species, and landscape connectivity that still matters. Groups like Basin & Range Watch argue that calling the site “disturbed” understates its environmental importance.

Both positions appear in the public record. And the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), as it operates today, does not resolve that disagreement early.

Instead, the core question “does this project belong here at all?” often gets answered late, after years of environmental review, revisions, and litigation risk. That is not because CEQA is ineffective. It is because CEQA is a process law, not a siting law.

CEQA requires agencies to study environmental impacts and mitigate them where feasible. It does not establish clear, statewide rules about where utility-scale clean energy should go first and where it should not go. Those decisions are left to planning efforts, agency discretion, or project-by-project fights.

Soda Mountain shows what happens when that clarity is missing.

The project has already gone through federal review. It is now undergoing a consolidated state review. And still, the central disagreement remains unchanged.

That suggests the issue is not simply speed.

It is alignment.

California has set ambitious goals to protect desert ecosystems and rapidly expand clean energy. Those goals are compatible. But the permitting system often treats them as competing priorities, because it does not consistently reward low-conflict siting or clearly discourage high-conflict siting early in the process.

Projects on clearly disturbed land. Closed landfills, remediated industrial sites, abandoned mines, degraded rights-of-way can still face long and uncertain review. Meanwhile, projects in ecologically sensitive areas can spend years advancing before a firm judgment is made about whether they should proceed at all.

The result is delay without resolution.

Soda Mountain is not proof that solar development is inherently incompatible with desert conservation.

It is proof that California decides too late where large energy projects should be built.

Other states have taken different approaches. Texas, for example, paired transmission planning with geographic prioritization, deciding where development made sense and then building infrastructure accordingly. California has experimented with similar ideas in limited contexts, such as the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan, but has not made this approach the default for utility-scale energy statewide.

As a result, projects like Soda Mountain become prolonged test cases instead of predictable decisions.

This is why CEQA reform matters.

Modernizing CEQA does not mean weakening environmental review. It means making critical decisions earlier, with clearer standards and fewer gray zones.

A modern CEQA should reform five things clearly.

First Reform: Create a true fast lane for utility scale clean energy on disturbed land by formally designating and mapping brownfields, landfills, retired industrial sites, mine lands, and degraded corridors, with upfront programmatic review that projects can tier off.

Second Reform: Make that fast lane outcome-based, trading shorter CEQA documents for standardized mitigation, enforceable performance standards, and real post-construction monitoring.

Third Reform: Add a desert siting tripwire so projects proposed on intact desert trigger early alternatives analysis and a fast decision on whether the location is appropriate at all.

Fourth Reform: Plan generation and transmission together by pre-clearing clean energy corridors and tiering project review off corridor-level CEQA instead of fighting site-by-site.

Fifth Reform: Align state and federal review on public land with one document, one schedule, and one public record so projects don’t bounce between NEPA and CEQA.

It means creating a permitting system that clearly says: if a project is sited on already damaged land, the review should be focused, predictable, and strict about mitigation and monitoring. And if a project is proposed on intact desert with meaningful ecological function, the system should decide quickly whether that location is appropriate, not years later, after trust has eroded across the board.

This is messy, every

Soda Mountain shows the cost of not doing this.

The process repeats.

The paperwork grows.

And neither clean energy nor conservation gets what it needs.

Protecting ecology while producing cleaner energy isn’t easy. But they are necessary conversations to have.

This isn’t an argument for or against Soda Mountain itself.

It’s an argument for fixing the system that keeps producing Soda Mountains over and over again.

Thank you for reading! I highlight threats to public lands and the energy industry’s impact. I believe clean energy is the future, and ALL energy projects should prioritize private land first to keep wild places wild. When energy extraction is needed on public lands all projects must restore the land after extraction. Public lands are unique and once lost, they’re gone forever.

Sources:

BLM - Biological Resources Technical Report

US Department of Interior - Interior Department Approves 287-Megawatt Soda Mountain Solar Project in Southern California

Basin & Range Watch - Soda Mountain Solar Project 2.0 Will Harm Desert Bighorns and Wildflowers

Stanford Law School - Analysis of CEQA Requirements for Soda Mountain Solar Project

BLM National NEPA Register - Soda Mountain Solar

CA Gov CEQA - Soda Mountain Solar Project

Sierra Daily News - Soda Mountain Solar Project Threatens Protected Mojave Desert Bighorn Sheep Populations